When Did Reading and Writing Become Common

This content contains affiliate links. When yous buy through these links, nosotros may earn an affiliate committee.

The history of reading is a topic that probably interests all readers. Reading what someone else has written brings with information technology a sense of continuity and solidarity. This sense of solidarity is strengthened when we become to know how others read. What we read and how it affects us tin reflect our personalities and our experiences equally individuals. The history of readers and reading can offer much insight into the nature and history of the society every bit a whole. The topic is a fascinating one, and one that has several absorbing aspects. Join us equally we endeavour to construct the bare bones of the process of the development of readers and reading over the course of history.

Very Practical Beginnings

In the 4th Millennium BCE, with agricultural prosperity and increasing complexity of social structures, urban centers started developing in Mesopotamia and an unknown individual changed the form of homo history by using some squiggles on dirt to represent a caprine animal and an ox. There, at the nativity of the concept of writing – the representation of spoken sounds using visual signs – its inseparable twin, the fine art of reading, was also born. Writing was initially used to keep records of transactions that involved several entities and were carried out across vast distances. The earliest known clay tablets used moving picture-like signs to depict lists of appurtenances.

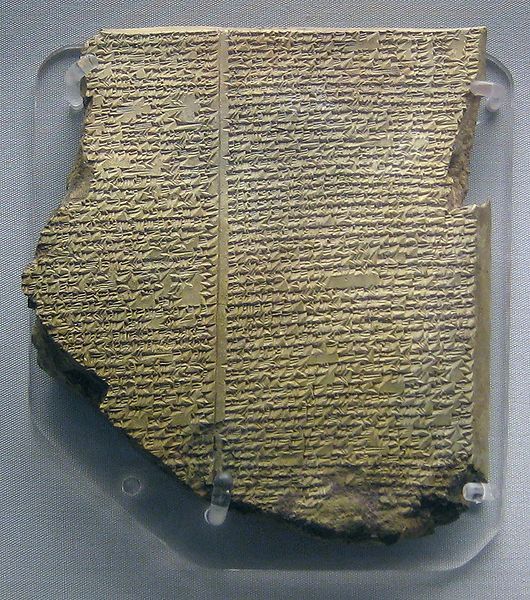

Around 2600 BCE, the cuneiform script developed and writing became more than versatile. Information technology was used to document laws and narrate deeds of kings, in add-on to keeping records of transactions. In the cuneiform script, each syllable was represented by a different sign, and the number of characters one had to larn in society to be able to read ran into hundreds. To be a scribe in aboriginal Mesopotamia was an enormous accomplishment. If a king could read, he made certain to avowal about it in his inscriptions. An elaborate system of schools trained immature scribes from an early historic period. The ancient pioneers of writing and reading were aware – and in awe – of the potential of this new form of communication. In ancient Mesopotamian culture, birds were considered sacred because the marks their feet made on wet ground resembled cuneiform characters. The patterns made by the wandering feet of birds were believed to be messages from the gods, waiting to exist deciphered.

As the aboriginal writers discovered their power to make and modify myth and history, the kickoff works of literature were written. The primeval known writer named in history is a woman, the Akkadian princess and High Priestess Enheduanna, who composed temple hymns around 2300 BCE and signed her name onto the dirt tablets on which she inscribed her works. It was around this fourth dimension that writers began to explicitly address the absent "honey reader" in their writings in specific acknowledgement of reading every bit a way of inter-temporal advice.

Reading equally Performance

The earliest written texts were meant to be read out loud. The characters were written in a continuous stream, to be disentangled past the skilled reader when reading out loud. Punctuation was used for the commencement time but around 200 BCE, and was erratic well into the eye ages. The masses were still illiterate, and written material merely reached them through public readings. Public readings took identify in majestic courts and monasteries. The performances of jugglers and storytellers were in vogue in the 11th and 12th centuries CE. Reading from a volume was considered pleasant dinnertime amusement, even in humbler homes, from the Roman times to the 19th century.

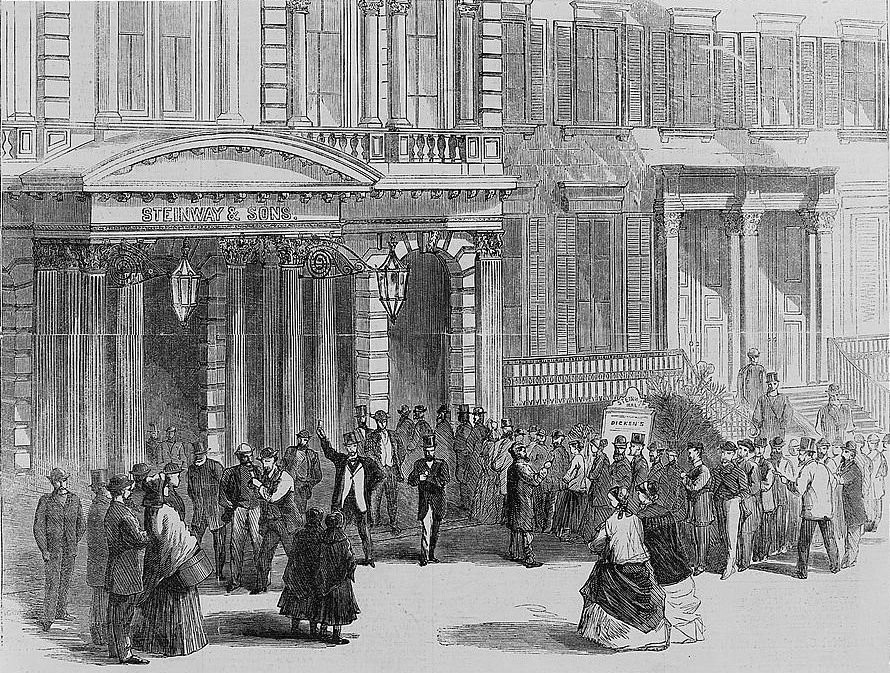

In the 5th century BCE, the famous Greek historian Herodotus used the platform of the Olympics to read his latest works. Authors' readings were a social convention in Rome equally early on as the first century CE. Public enthusiasm for these readings might have waxed and waned beyond centuries, simply the tradition has endured. Popular authors have embraced this tradition with varying degrees of fervor, ranging from Charles Dickens'due south carefully planned readings to the uninterested monotones of others. For some authors, like Jean Jacques Rousseau, whose works had been banned by the pre-revolutionary French authorities, readings at the houses of friends was the only mode to seek an audience.

Even as education became more than widespread, beingness read to was a major avenue for entertainment and acquiring knowledge, particularly for women. Well into the 19th century, women were encouraged to acquire only very minimal education, and their scholarly ambitions were frowned upon. Being read to by family and friends was acceptable, and provided women some semblance of an outlet for their curiosity and hunger for stories. Once master education became more accessible and acceptable, younger members of the family unit read to the elders, in a sweet reversal of the classic grandma's tales.

Reading Silently

Given how early on texts were meant to exist heard rather than seen, the act of reading silently remained a curiosity. In 330 BCE, when Alexander the Great silently read a letter from his female parent in front of his troops, the already nonplussed men were further stunned past their general's otherworldly capabilities. Much later, in his Confessions, written in 4th century CE, St. Augustine marvels at how his mentor, St. Ambrose, managed to grasp the meaning of a text while "his voice was silent and his tongue was nonetheless". The showtime regulations requiring scholars to work in silence in monastic libraries engagement from the 9th century. The ancient and medieval libraries until and so, and probably for a considerable time afterwards that, would have been very different to the modern concept of a quiet place to study. Next time you daydream about reading at the library of Alexandria or the library of Celsus (who doesn't, correct?), do not forget to factor in the din from the very loud scholarly explorations going on around you.

With increased literacy, better punctuation, and books that were fabricated accessible to the general public past the inclusion of pictures or the simplification of language, silent reading became the norm. More than and more than readers began to be able to course a personal connectedness with the written text, without someone else's voice and estimation interim as intermediaries. Silent reading made reading a individual activity – making room for more options in the choice of a reading nook. Chaucer recommended reading in bed in the 14th century, Omar Khyyam and Mary Shelley advocated outdoor reading, while Henry Miller and Marcel Proust preferred the absolute solitude of the bath.

Print Revolution

The primeval printing technology originated in Cathay, Japan, and Korea. The imperial land of Communist china produced a large book of printed material, printed by rubbing newspaper against inked woodblock, to sustain its extensive bureaucratic system. The knowledge of print engineering reached the western globe around the 13th century, and woodblock printing attained widespread popularity by the 15th century. The increased ease at which books could be produced by printing, the durability of the final products compared to handwritten manuscripts, and the always-rising need for books led to further interest in the development of new printing techniques. In the 1430s, Johannes Gutenberg developed the first mechanical press press at Strasbourg, Germany. The press was operational in Mainz past the 1450s, and was printing copies of what would later come to be known equally the Gutenberg Bible.

One time the inevitability of the eventual ubiquity of impress and reading became apparent, churches all over Europe embarked on a spree to educate the masses, and through the establishment of village schools, literacy grew. Booksellers printed copies of popular ballads and folklores to increase public appetite for their wares. Small, cheap editions similar the English language chapbooks and French Biliotheque Bleue were peddled by travelling salesmen. Periodicals started existence published in the early 18th century, increasing further the population of defended readers. Information technology was around this fourth dimension that the novel as a literary form took house root in French republic and England. When, in 1849, Charles Dickens'due south Pickwick Papers was serialized in a magazine, the allure of the novel was combined with the affordability of magazines, and readers could live in the story for months.

Libraries

The Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal put together a library of clay tablets in Nineveh (modernistic-day Iraq) in the 7th century BCE. The collection was amassed at the meridian of the Assyrian empire, more often than not through plunder. The library housed original tablets dating back to the 2nd millennium BCE, featuring works written in both Sumerian and Akkadian. Specialized scribes were employed to produce copies of important works. Fiercely possessive of his collection, Ashurbanipal threatened anyone who dared misplace his books with terrible fates. Centuries afterwards, in 331 BCE, Alexander the Dandy founded the city of Alexandria in Egypt. Within years Alexandria evolved into a multicultural urban center with a circuitous bureaucracy. Alexander's successor, Ptolemy I, founded the library of Alexandria with the brusk-term purpose of organizing the vast reams of documents that had been stockpiled in the city, and the ostentatious long-term purpose of housing all the cognition in the world. In society to reach this goal, all ships stopping at Alexandria had to give up all books on lath to be copied (or retained) at the library.

The history of cataloguing or organizing written textile is even older than the very beginning formal libraries. In the ancient Sumerian language, record keepers were called "Ordainers of the globe". The first ever catalogue of books is the catalogue of the Egyptian "Firm of Books" dating back to 200 BCE. The library of Alexandria was the laboratory for a lot of early experiments in library science, mainly through the works of Callimachus of Cyrene, who catalogued the library of Alexandria in the 2nd century BCE. He arranged titles into lists, or pinakoi, according to categories including drama, lyric verse, legislation, history, medicine, philosophy, and miscellanies. He was also the start librarian in history to utilize an alphabetical ordering for arranging the books within these genres. Though libraries remained highly exclusive spaces for centuries later on these developments, attainable and useful only to privileged and skilled scholars, the concept of a comprehensive library catalogue would prove invaluable to generations of readers roaming the aisles of these storehouses of information in search of knowledge.

The establishment of lending or circulation libraries, coupled with the advent of new press technologies, were developments that revolutionized reading for common people. The 18th century saw a proliferation of these institutions that actually allowed readers to take items in their drove home, both in Europe and in North America. Readers made utilise of this opportunity individually, also equally collectively past organizing themselves into reading groups and book clubs.

Reading as Rebellion

Every bit we take seen so far in our brusk exploration of the history of reading, the power of the written word, which is in turn transferred onto its readers, has been recognized since ancient times. It is therefore no surprise that authorisation figures throughout history have tried to prevent the people they oppress from accessing reading material and even literacy. For these marginalized groups, reading, against all odds and in severely adverse circumstances, has been a courageous act of rebellion and resistance.

Enslaved people, both in the dominions of the British Empire and in the Americas, were denied access to reading for centuries. They still managed to learn to read, frequently risking their lives in the process – unobserved and using ingenuous methods of learning. The literature that many of these people taught themselves to read and write went on to become a potent weapon in their battle against slavery and oppression.

Women's reading and intellectual ambition was discouraged, frequently violently, in societies all over the world, despite some of the earliest poets and authors having been women. Yet, largely cut off from the outer world and forced into the routines of domesticity, generations of women taught themselves to read and write. They wrote copious volumes about their own experiences, many of which stood the test of fourth dimension and are at present recognized as classics. Women in Cathay and Japan invented their own dialects used specifically for communication betwixt women. In India, Rashsundari Devi, the author of the first autobiography in Bengali, taught herself to write by scribbling letters in the soot left over in the traditional woods burning oven after the day's arduous cooking. All-women book clubs that discussed literature from the female person point of view take been mentioned as early equally the 15th century, in the French volume about medieval women'south beliefs, The Distaff Gospels (Les Evangiles des Quenouilles).

Totalitarian rulers accept always recognized the importance of ignorance in keeping people subservient to exploitative regimes, and accept been placing blanket bans on books that get against the version of reality that they wish to project, with gusto that has been undiminished by history. The works of Protagoras were burned in ancient Athens; Chinese emperor Shih-Huang Ti wanted to burn down everything written before his time then that history began with him. In 1559 the Roman Catholic Church building began maintain an Index of Forbidden Books. In Nazi Germany, the authorities propaganda automobile made a spectacle of book burning, with each volume being burnt receiving its ain individual epigram. Colonial rulers tried to ban and prevent the circulation of printed material that would question the legitimacy of their rule in colonies all over the earth. The power of the written word has also been misused, and is still being misused, to spread imitation information and hatred.

But the international community of readers has endured. At a large calibration they accept shown themselves equal to the responsibility that comes with the power of existence readers. Over the grade of history readers have demanded better from the things they read – and have gone ahead to write it themselves.

The primary reference consulted in writing this article is A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel, a delightfully well-written account of the evolution of the reader through the ages. For more bookish history, bank check out this postal service well-nigh the history of cookbooks and this i almost why books evolved to be the rectangles that we are accepted to now. Interested in aboriginal libraries that you can still visit? Check out our roundup hither.

Source: https://bookriot.com/history-of-reading/

0 Response to "When Did Reading and Writing Become Common"

Post a Comment